‘The poor get richer’

By Julie Luxton on November 15, 2021 in Curriculum

Vocabulary knowledge and enrichment in Aotearoa NZ secondary classrooms

‘The rich get richer and the poor get poorer’. We’ve all heard of the Matthew Effect. Students who read more become better readers. Those who read less (or not at all) do not. It’s a no-brainer.

The Matthew Effect was referenced in the vocabulary context by Aaron Wilson who co-ordinated the Secondary Literacy Project back in the day. He described the ‘vicious cycle of unintended consequences’ when written texts or spoken instructions are simplified for identified learners, thereby reducing their exposure to new vocabulary and unintentionally increasing the lexical gap between these learners and their peers.

Vocabulary matters. International research over many years indicates a relationship between vocabulary knowledge and secondary school achievement. There’s also plenty of evidence that vocabulary knowledge contributes significantly to reading comprehension performance – especially for expository texts.

Vocabulary size research in our schools

When working in schools, I have often heard teachers express concern about the vocabulary poverty of their students. This is especially so for those from low socio-economic backgrounds, who have fewer opportunities for the variety of experience which enriches our vocabulary.

There’s not a lot of research into the vocabulary of secondary school students in Aotearoa NZ. One project was undertaken in eight secondary schools in Palmerston North and Wellington with 243 13 to 18-year-old native speakers of English (Coxhead et al., 2015). The researchers concluded that teachers did not need to worry about the ‘general purpose vocabulary knowledge’ of their students, except in ‘a very small number of cases’ (p. 21). VST scores indicated that most students had a sound receptive knowledge of 9000 high-frequency and mid-frequency English words – sufficient to comprehend newspapers and novels as diverse as The Hunger Games and Pride and Prejudice (Coxhead, 2012). Therefore, the researchers said, teachers should be encouraging students to read a lot and focusing on subject-specific words. It is noteworthy, however, that this research was conducted in decile 6-10 schools and English language learners were deliberately not included.

Digging deeper

Vocabulary size is an interesting concept – especially for this word nerd. Students we assessed were genuinely interested to find out the number of words they knew relative to age expectations – and their peers! But a more nuanced understanding is needed to inform teaching and learning. As well as ‘general purpose’ high and mid-frequency (1000 - 9000 words) and subject-specific vocabulary, there’s another, powerful group of ‘general academic’ words. Words like analyse, implement, justify, analyse, controversy, hierarchy, infrastructure. These occur across learning areas – with differing meanings and applications. Check out the Academic Word List or the New Academic Word List. These words are abstract, complex and hard to learn. They are also important. They make up around 10% of academic text (Coxhead, 2000) and have been said to constitute a ‘lexical bar’ which has to be crossed by learners to achieve success in ‘conventional forms of education’ (Corson, 1995, p.181).

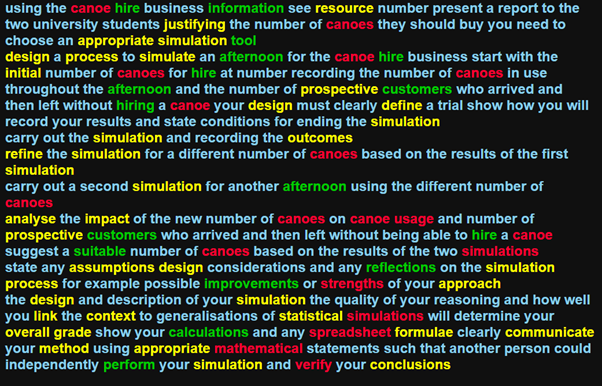

Academic words are particularly important in the NCEA assessment context. Check out this Vocabulary Profiler analysis of a TKI internal assessment task for a Level 2 NCEA Mathematics and Statistics Achievement Standard (91268) Investigate a situation involving elements of chance using a simulation. The yellow words are classified as academic and constitute almost 15% of the text! Yes, I know. Many of the same words are repeated, but this simply reinforces the need for students to understand them well.

What to do?

Incorporate more reading and writing opportunities in your classes.

Amplify , rather than simplify, vocabulary. Amplifying vocabulary involves using many and varied approaches to target words, such as direct teaching, short oral explanations, glossing or footnotes or hyperlinked word meanings, and using effective strategies like the Frayer model (and others mentioned below) to strengthen understanding.

Explicitly teach new vocabulary in context as it occurs – with a brief explanation of its meaning, analysing its parts, if appropriate, and its relationship to words already known.

Avoid introducing new vocabulary in lexical sets e.g. solvent, solute, solution, dissolve, or teaching opposites together, as this can be confusing for students.

Design small group activities which enable students to talk about, and use, new words.

Ensure that vocabulary learning opportunities are balanced across the four strands i.e.

meaning-focused input (listening and reading)

meaning-focused output (speaking and writing)

language-focused or direct learning e.g. pronunciation, spelling, different uses, word parts (prefixes, stems and suffixes), derivation and common phrases

fluency development i.e. being able to use target words readily, confidently and accurately.

Recycle new vocabulary using spaced repetition i.e. maximising encounters with target words when first introduced and ensuring retrieval and use opportunities over the next week.

Encourage ‘word consciousness’ i.e. an awareness of words and their functions, as well as an appreciation of the value and power of words.

Support students to become independent vocabulary learners.

Where to find effective practical classroom approaches and strategies

I’d start with these two resources:

Effective Literacy Strategies in Years 9 to 13: A Guide for Teachers (MOE, 2004)

An oldie but a goodie. This resource was recently recommended in the TOD Accord materials about new NCEA literacy requirements. It contains a wealth of practical strategies based on sound research. Chapter 2 (pp.32-49) provides clear explanations of strategies to:

introduce new vocabulary and draw on prior knowledge e.g. word maps

help students to solve unknown vocabulary e.g. using context clues, clustering, interactive cloze, structured overviews, clines

provide students with opportunities to use new vocabulary and assist retention e.g. concept circles, pair definitions, word and definition barrier activity, word games, picture dictation.

Check out the vocabulary section at this weblink. For each strategy there are instructions on use, a short video and some examples within a teaching and learning sequence. My personal favourites are vocabulary jumble, word clustering, concept circles and loopy aka ‘I have… Who has…?’

It’s funny the words that stick in your mind. I still remember from my long-ago school days that the German word for vocabulary is ‘Wortschatz’ – literally ‘word treasure’. A memorable and appropriate metaphor. Incorporating explicit vocabulary teaching and learning will help the word-poor become richer in our classrooms.

References

Corson, D. (1995). Using English words. Boston: Kluwer Academic.

Coxhead, A. (2012). Researching vocabulary in secondary school English texts: ‘The Hunger Games’ and more. English in Aotearoa, 78, 34-41.

Coxhead, A., Nation, P., & Sim, D. (2015). The vocabulary size of native speakers of English in New Zealand secondary schools. New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, 50(1), 121-135.

Greene, J. & Coxhead, A. (2015). Academic vocabulary for middle school students: Research-based lists and strategies for key content areas. Baltimore, MA: Brookes Publishing.

Luxton, J., Fry, J. & Coxhead, A. (2017). Exploring the knowledge and development of academic English vocabulary of students in New Zealand secondary schools. Set (1), 12-22.

Nation, P. (2012). The Vocabulary Size Test. Retrieved from https://www.wgtn.ac.nz/lals/resources/paul-nations-resources/vocabulary-tests

Nation, P. & Coxhead, A. (2021). Measuring native-speaker vocabulary size. Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing.

Wilson, A. (nd) Vocabulary in the secondary classroom. Woolf Fisher Research Centre

Get in touch with Julie today to learn more

Other articles you might like

I'm a country girl. So when I turned 18 and moved to Auckland, it took some adjusting to. One of the biggest challenges was trying to navigate the place. It was huge. I can remember many times driving around, not really knowing how to get to my destination, but hopeful of spotting something familiar, a street name or a landmark. I often got lost, and when I did I would just head towards the sky tower and hope for the best. I relied a lot on remembering things from previous journeys and sheer luck in those early days.

I, for one, am heartened by imminent changes to the NCEA literacy assessment requirements. I’ve always been uneasy about the current expansive pathway, with hundreds of tagged achievement standards from a wide range of subjects, most of which assess content knowledge, with no literacy-specific criteria.

“The limits of my language mean the limits of my world”- Ludwig Wittgenstein.