Science capabilities

By Editor on April 9, 2019 in Curriculum

What is their potential to refocus science education?

According to the New Zealand Curriculum, students learn science at school so that “they can participate as critical, informed, and responsible citizens in a society in which science plays a significant role” (p17). The quick way of saying this is that the purpose of school science is to develop scientific literacy.

Traditionally, school science has focused on the delivery of content knowledge. If the aim of learning science at school is to develop scientific literacy, then programmes also need to include opportunities for students to engage with the practices of science, and to connect their science learning with their life outside of school. Nurturing curiosity, encouraging questioning, developing a respect for evidence, and an appreciation of the tentative nature of science should be key drivers of school science programmes.

Both the inclusion of the Nature of Science strand as the compulsory strand of the science learning area in the NZC and the development of the Science Capabilities were attempts to focus learning and teaching in science on the development of scientifically literate citizens. Many teachers have enthusiastically picked up the idea of science capabilities as a focus for their teaching, and many are now exploring ways of assessing them. A lot of really good things are happening. But it also seems we still have a long way to go if we really want to shift the focus of school science from simply being about “knowing a lot of stuff” to “using scientific knowledge and skills and ways of thinking to make informed decisions”. If, at even an unconscious level, we still believe the real purpose of school science is the acquisition of abstract knowledge then the risk is that the science capabilities become simply more stuff to be learned (just as we saw commonly happen with the Nature of Science strand).

If we focused on science capabilities as a tool for teachers to think about the learning opportunities they provide (and specifically the questions they ask), rather than thinking about them as abilities students are developing, would they be more useful for reframing science education to focus on the development of scientific literacy?

In the Five science capabilities resource on Tāhūrangi, there are examples of the sorts of questions that can be used to develop different science capabilities. They are a few clicks away from the introductory page; you will find them under each capability where it says “learn more”. For example, under Using Evidence, it says:

Students should be encouraged to ask and answer questions such as:

How do you know that?

What makes you think so?

How could you check that?

So an example of this would be…

Can you think of an example when this wouldn’t work?

These certainly are the sorts of questions we want students to be asking, but in the first instance, maybe it would be more helpful if the focus was on teachers asking these sorts of questions. The sorts of questions you ask help to shape the learning-focused culture of the classroom. If the classroom culture is one where critique is encouraged and expected, then students will be experiencing what it is like to do science and will also be engaging in powerful pedagogical practices for learning science. A focus on developing scientific literacy does not mean knowledge is no longer important – we want students to engage with the big ideas of science and the practices of science.

The sorts of questions you ask, and the talk you encourage in your classroom, show what is valued. Put some examples of the sorts of questions to ask up on the classroom walls – just to remind you. Over time, these will also act as a support for students asking questions of each other and themselves.

It’s also important to be aware of what behaviours you are noticing and providing feedback on. Is your feedback to students focused on when they get an answer correct or is it when they generate new questions, question other students’ ideas, or change their minds when new evidence comes to light? Do you use, and encourage students to use, tentative language such as might, could be, perhaps, likely? Openness, suspending judgment and accepting science’s provisional nature are all at the heart of scientific inquiry and if you are using this sort of language you are modelling an aspect of what it means to engage with science.

Imagine a classroom where the teacher was constantly encouraging everyone to:

Differentiate between observations and inferences;

Back up their ideas with evidence;

Evaluate the trustworthiness of data;

Critique the way ideas are represented;

Engage with science.

What would you hear the teacher saying? What are the questions that would be asked?

How much like you is this teacher? One way of starting to answer this last question is to record yourself talking with students. You don’t need to share the recording with anyone else. Just listening to yourself can be a very powerful learning experience. What we say and what we think we say can be quite different things!

References:

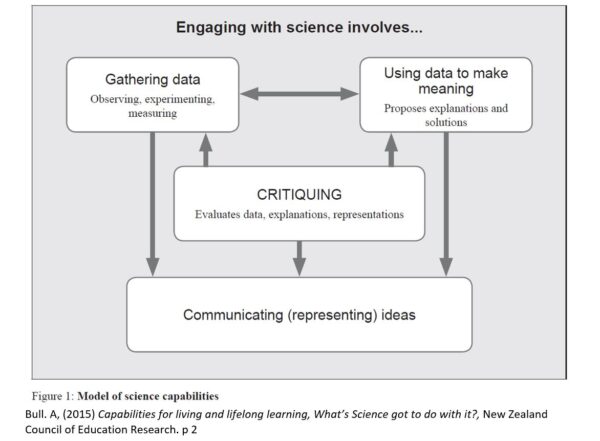

Bull, A (2015) Capabilities for living and lifelong learning: What’s science got to do with it? New Zealand Council of Education Research

Ministry of Education, NZ. (2007) The New Zealand Curriculum. Wellington, New Zealand: Learning Media.

Tāhūrangi (n.d.) Five science capabilities, retrieved from https://newzealandcurriculum.tahurangi.education.govt.nz/five-science-capabilities/5637164183.p

Other articles you might like

There is now widespread agreement in the scientific community that unless we reduce carbon emissions substantially, and quickly, the planet is likely to become uninhabitable in the not too distant future.

A great starting place… But then what?

I struggle to understand why science is very largely absent from primary school teaching.