Niho Taniwha: A practical guide to culturally responsive teaching

By Laura Stutz on April 9, 2025 in Cultural capability

In this blog, Laura shares insights into how the Niho Taniwha framework can guide educators to create learning environments where ākonga Māori can be Māori.

What does it truly mean for ākonga Māori to thrive in your classroom?

Not only included — but seen, heard, and valued as Māori.

Culturally responsive teaching is more than a set of practices — it’s a mindset, a commitment, and a continuous journey. In Aotearoa, the Niho Taniwha framework offers a powerful guide for walking this path with tika, pono, and aroha.

Creating culturally responsive learning environments

As educators, our mission is to cultivate learning spaces that honour and empower all students. In Aotearoa, aligning our teaching practices with Niho Taniwha—a framework from te Ao Māori — offers a culturally responsive approach that supports ākonga Māori to thrive. Niho Taniwha offers a structured pathway to integrate meaningful, student-centred teaching strategies. But how do we practically apply this framework?

Let’s explore its key concepts and guiding pātai to support your journey.

Understanding Niho Taniwha

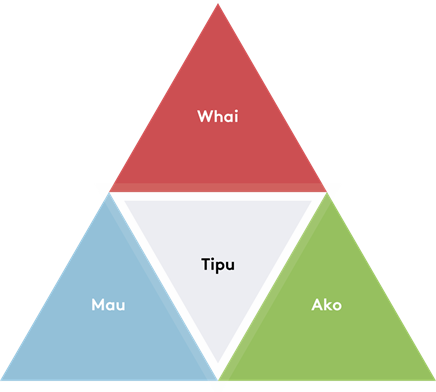

Niho Taniwha, meaning "the teeth of the taniwha," symbolises strength, connection, and interdependence. Developed by educational leader Dr Melanie Riwai-Couch, the framework is structured around four interconnected phases that guide educators in fostering Māori success as Māori. These are:

Whai (Pursue) – Identifying the motivations for improvement and surfacing key values and beliefs.

Ako (Learn) – Positioning ourselves as learners and engaging with research and best practices.

Mau (Grasp) – Implementing and evaluating what has been learned to enhance teaching and learning.

Tipu (Grow) – Reflecting on progress and identifying next steps for ongoing development.

When we commit to culturally responsive practice, we aren’t just changing our pedagogy—we're changing the learning environment itself.

As Melanie reminds us in Niho Taniwha, “by embedding the principles of Niho Taniwha, we create spaces where Māori students see themselves reflected, valued, and supported—not as an exception, but as the norm” (2021).

1. Whai: Identifying and pursuing improvement

The first step in this process is self-reflection. Educators must critically assess their values, beliefs, and current teaching approaches. Consider these strategies:

Actively listen to the lived experiences of ākonga Māori to understand their aspirations. Every student wants to succeed, but their realities and pathways are unique. How can we support their journey?

Engage in whakaaro tuatahi (initial reflections) to surface key ideas for change. Are our teaching paradigms reinforcing deficit thinking, or are we fostering growth and potential?

Strengthen relationships with iwi, whānau, and Māori educators to ensure authenticity in teaching approaches. Regular, meaningful engagement with whānau fosters a learning-focused partnership.

Berryman, Lawrence, and Lamont (2018) emphasise that authenticity is central to culturally responsive teaching. Grounding our practice in Māori ways of knowing and being ensures that our approach is not only respectful but transformative.

2. Ako: Positioning ourselves as learners

Education is a reciprocal process - ako means both teaching and learning. To grow in our practice, we need to:

Engage with āria matua (core Māori education theories) and Aotearoa-based research. How often do we connect with kaupapa Māori in our professional learning?

Define kairangi (educational excellence) through Māori success indicators. What does research tell us? How might we measure success beyond traditional Western models?

Foster true reciprocal learning where both teachers and students share knowledge. This requires educators to be vulnerable, share power, and create spaces of aroha, tika, and pono.

As Macfarlane (2004) reminds us, when students feel genuinely valued in the classroom, their confidence and engagement grow. Culturally responsive practices that centre manaakitanga and relational trust are key to creating this environment.

3. Mau: Implementing and evaluating learning

Once we have learned, we must take action. For educators, this means:

Using aromatawai (assessment and evaluation) to measure the effectiveness of our teaching. What voices of ākonga Māori inform your reflections?

Implementing rautaki whakapiki (improvement strategies) to enhance student outcomes. What evidence-based approaches are we applying?

Holding ourselves accountable for continuous reflection and improvement. Are we embracing vulnerability in our learning process?

Te Hurihanganui: A Blueprint for Transforming Māori Educational Success highlights the importance of embedding learning within Aotearoa’s cultural and physical landscapes. When local context and identity are intentionally woven into the curriculum, students connect more deeply with their learning and see their own world reflected in the classroom.

4. Tipu: Reflecting and growing

Growth requires ongoing critical reflection. Ask yourself:

What changes have I made, and how have they impacted my ākonga Māori?

What challenges have arisen, and how can I address them?

What is my next focus area for improvement?

How can I further involve ākonga Māori and whānau in my learning journey?

By regularly revisiting these questions, we ensure continuous growth and deeper alignment with Niho Taniwha principles.

Moving forward with Niho Taniwha

Aligning teaching with Niho Taniwha is not about adding tokenistic Māori elements; it is about fundamentally shifting how we approach education. By integrating whai, ako, mau, and tipu, we cultivate learning environments that celebrate Māori identity, knowledge, and success.

Start small. Seek guidance. Reflect often. By embedding Niho Taniwha into our teaching practice, we help create an education system where ākonga Māori can thrive as Māori, strengthening not just individual learners but entire communities.

References

Berryman, M., Lawrence, D., & Lamont, R. (2018). Culturally responsive teaching and learning in New Zealand classrooms. Waikato Journal of Education, 23(1), 21–34. https://doi.org/10.15663/wje.v23i1.635

Ministry of Education. (2004). Ka hikitia: Managing for success – The Māori education strategy. https://www.education.govt.nz/assets/Documents/Ministry/Strategies-and-policies/Ka-Hikitia/KaHikitia2009.pdf

Ministry of Education. (2020). Te Hurihanganui: A blueprint for transforming Māori educational success. https://www.education.govt.nz/assets/Documents/Te-Hurihanganui/Te-Hurihanganui-A-Blueprint-for-Transforming-Maori-Educational-Success.pdf

Riwai-Couch, M. (2021). Niho taniwha: Improving teaching and learning for ākonga Māori. Huia Publishers.

Join us at the Niho Taniwha conference on 12 and 13 May 2025 and continue the journey with others committed to transforming Māori educational success.

If you have any questions about this article

Other articles you might like

A personal reflection on the last 40 years, the progress made and how we can build upon that.

"As educators, we need to comprehensively understand Te Tiriti, the history and its ongoing impacts; and to continue to strive for what we know is important: for excellence and equity for ākonga Māori and all learners."

This blog explores the meaning of cultural competency in education and its impact on creating inclusive learning spaces for all ākonga.