From classroom teacher to staff room teacher

By Richard Watkinson on October 18, 2018 in Assessment for learning

The first day at school all over again.

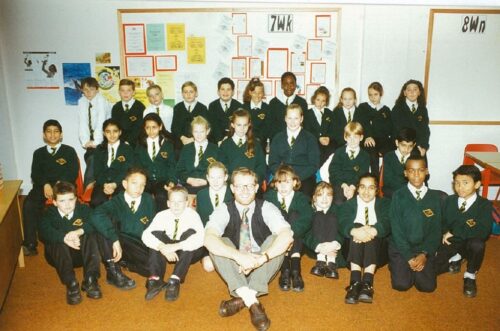

I began my career as a secondary English teacher in Nottingham in the UK in 1993. I was full of idealistic good intentions and saw teaching as a way of promoting social justice and equity. I began work in a school with plenty of opportunities for promoting social justice and equity as it was located in an inner city community that had, historically, been one of the poorest in the country. I was determined and (it turned out naively) confident that I would be able to make a difference and threw myself into planning exciting lessons based on challenging and innovative texts. I had a mixed ability Year 10 English class who were beginning their GCSE course. Here was where I would make my mark!

It took only took a week for my bubble to be well and truly burst by a major fight in Period 5. Claire threw a chair at Shameen and it was all on for young and old. I called in the cavalry in the form of a formidable deputy principal and order was restored. But it was only the beginning. Over the next few weeks, equipment was thrown across the room, students swore at me, and my early optimism soon faded.

Fortunately, I was not left alone to solve the problem of developing good learning relationships with my students. I worked with a mentor to carefully design a unit of work which we planned to team teach to the Year 10 class.

The first lesson teaching the new, carefully planned unit was on Monday morning. A good time, one might suppose, to engage the students. And, to be fair, it was all going well as the students discussed the work. I was circulating the room listening to and contributing to the discussions. At one table I was becoming particularly animated and one girl looked me in the eye and pronounced, “Sir [a nice touch that!] you’re talking out of your a**e.”

My hard work continued with the class and though I never quite won them over, I never gave up either. I kept planning what I hoped were engaging lessons and I kept responding to the work they produced with positive comments about what they had achieved and what their next steps might be. I kept discussing strategies to promote their learning with my mentor.

I can’t remember how they went with their GCSE English results but I can remember meeting Claire (who had the fight in my second week) a couple of years after she had left school. Claire told me that she was training to work in early childhood education and enjoying herself and that her time in my class had not been wasted. We passed a few more moments in pleasant conversation, something we had rarely achieved in the two years she was in my GCSE class.

Somehow, I had managed to establish a relationship with Claire and, perhaps, with other students in the class, through my methodology of planning engaging activities using interesting and relevant resources that were appropriate for the next steps in learning. I added to and adapted this methodology over the next 25 years and as a result have managed to build positive learning and personal relationships with students. A key refinement has been gathering more information so that I “know my learners” from multiple perspectives and sources. Now I seek to know about, for example, students’ literacy learning needs and how their cultural identity impacts on learning. I have also learned to find out from my students how their learning is going so that, rather than “hoping” to plan engaging lessons, I know their interests and strengths and how to address weaknesses in a responsive way.

So, fast forward to January 2018 and a new “first day at school”. Now my role is as a PLD facilitator with Evaluation Associates. This time my class is made up of teachers. What are the similarities between this first day and the previous one in 1993? What are the differences? What knowledge and expertise can I bring from the lessons I learned during and after my first day as a teacher to my new role as a facilitator, as a teacher of adult learners? What new knowledge and expertise do I need to develop? How will I develop positive learning and personal relationships with my new learners?

My efforts to build relationships begin with my pepeha (a new addition, we didn’t do pepeha in Sneinton!) and still include humour. After my pepeha, I explain that I now live in Mangere Bridge in South Auckland and claim that it is “the second most beautiful place to live in New Zealand after . . . [insert name of the town in which I am presenting].”

Getting people up and active helps to break the ice and generate personal connections. I ask teachers to organise themselves on a continuum of years of experience and on one occasion a wag observed to his veteran colleague, “You should be standing in the car park, mate!” Hearing that story allowed me to put a name to a face in the crowd and develop the joke into a discussion about what all those years of experience had taught him.

A significant challenge is to work out ways of establishing teachers’ current levels of understanding. I don’t have any achievement data for them. Asking teachers to self-assess their knowledge of, for example, Teaching as Inquiry and organise themselves on a physical continuum in the staffroom is engaging and responsive. It encourages to begin to explain the reason or evidence for their self-assessment to the person next to them on the continuum.

Finding out that one teacher had placed himself at the expert end of the Teaching as Inquiry spectrum because he mistakenly equated it with inquiry learning reminded me of the importance of clarifying the difference between the two processes (or any other concepts on which I want people to self-assess) to prevent misunderstandings. Seeing the line-up allows me to get an overview of the teachers’ (self-reported) levels of understanding. Take a photograph and repeat the process at the end of the day and I have a way of checking the impact of my work.

Just after I started my new job, Dylan Wiliam, guru of formative assessment, delivered a workshop in Auckland that emphasised the importance of formative assessment in teaching and learning. PowerPoints now begin and end with learning intentions and success criteria and my facilitation includes whole class feedback techniques to help gauge teachers’ levels of understanding. The challenge is to create what Wiliam calls “hinge questions” at key moments in a lesson or sequence of learning. When the intention is to move from one key idea/activity/point to another and understanding of the current point is a prerequisite for the next step in learning, hinge questions are vital.

Like learning to teach, learning to facilitate is not a solo practice. There are colleagues to work with and learn from. And, because the company is founded on open to learning principles, feedback conversations are always honest, respectful and, therefore, extremely helpful. Furthermore, in-depth work by a team of facilitators and academics through the University of Auckland has led to the elaboration of a collection of professional practices called Deliberate Acts of Facilitation or DAFs. The DAFs, like the Deliberate Acts of Teaching (DATs), describe discrete but connected dispositions and acts that promote learning.

The DAFs are not an instruction book for facilitation. Rather, the winning formula, in line with the notion of adaptive expertise that informed the research, is to choose the right act at the right time. For me they are a vital touchstone for where I want to progress with my facilitation. They are (highly aspirational) success criteria.

So what are the differences and similarities between my two “first days of school”? So far, teachers haven’t thrown chairs at me or each other, etched abuse on any of the handouts I have provided, or accused me of talking out of my a**e. In fact, in workshops and teacher only days, teachers tend towards the polite and passive. Good manners and the desire to avoid conflict mean that teachers/adult learners don’t display their lack of engagement and understanding in the same way as adolescents. And in some ways that makes the job of more difficult because there isn’t any immediate feedback (in the form of flying chairs) when it isn’t working. I need to develop strategies to promote engagement and understanding, check they are working, and be responsive to the current levels of knowledge and understanding of teachers in relation to the subject about which I am presenting or facilitating.

I notice that the first part of this narrative describing my formative experiences as a teacher is much longer than the second part describing my formative experiences as a facilitator. Perhaps I will have more to say in part two – after 25 years work as a facilitator?

Other articles you might like

Schools are increasingly focused on placing their learners at the centre. And there is plenty of research that tell us this is a very good thing!

A few years ago I visited a school for the first time and a teacher asked what my job was. I told her that I was a facilitator and a lot of my work in schools was supporting teachers and students with assessment for learning. “Ugh… assessment,’ she replied. “If they would just let us get on with teaching!” It was a wonderfully honest response, which demonstrated to me how assessment can start to be viewed as a required task which sits separately to teaching and learning, rather than the bridge between teaching and learning.

There’s excitement in the air as teachers in large cities and small rural schools realise how to enact the New Zealand Curriculum in its full glorious intent by developing a student-centred approach to teaching, learning and assessment. This lies at the very heart of the New Zealand Curriculum.