A recipe for success in secondary school PLD

By Editor on May 20, 2019 in Assessment for learning

It’s Monday afternoon and teachers are slowly and begrudgingly making their way to the staff room for the fortnightly “PD session”.

It’s winter, cold, dark and wet and as the crowd grows, so does the atmosphere of reluctance. Meanwhile the deputy principal in charge of PD, who has spent the day sorting out a dispute between a group of Year 10 girls that started on Instagram and has now, literally, “gone viral”, has just remembered that she is running the session. She hastily checks out TED talks and find something by Ken Robinson vaguely connected to the intent of the session. “That will get them talking” she thinks, optimistically, and hurries off to connect her computer to the data projector. “Now, where is that speaker we used last time . . .”

That scenario for professional learning and development (PLD) is probably familiar to many secondary school teachers. By way of happy contrast, here is an account of a medium sized, high-decile, co-ed school that took a different, and refreshingly successful, approach to whole staff PLD.

The school was determined to raise achievement. The leadership team focused on increasing the number of Merit and Excellence endorsements in all subjects and at each level of NCEA. They also set targets for achievement in Scholarship. The school’s participation in a Kāhui Ako offered two key affordances: 40 hours of centrally-funded PLD plus the time, experience and expertise of five within-school-leaders, or iCoLs.

Where were we going?

A PLD programme was planned and implemented. Subsequent evaluation showed significant positive impact on:

teacher engagement with the aims, process and content of the PLD

teacher knowledge and understanding;

teachers’ mindsets

teachers’ self-efficacy about providing feedback that promotes further learning.

The senior leadership met with me and we began to explore our theories for raising achievement at the school. We agreed that for students to be successful, they needed to know the answers to these three questions about their learning:

Where am I going?

How am I going?

Where to next?

We agreed that the answers to questions two and three could be provided by effective feedback that promotes further learning and so we discussed ways to develop a feedback culture at the school.

How were we going?

Fortunately, the school’s timetable included a whole staff PLD session every Wednesday morning. The Across School Kāhui Ako leader, who is also a deputy principal, hoped to raise the profile and the “leading learning” skills of the iCoLs. We agreed that the iCoLs would meet with the facilitator to plan ten PLD sessions that would be delivered in Term Two. Each iCoL would work with a cross-curricular Professional Learning Group (PLG) of 8 to 10 teachers to introduce the theory and practice of effective feedback.

The process was further refined during a couple of meetings before the planning began in earnest. We co-constructed goals and outcomes for the PLD including developing the leadership capabilities of the iCoLs; developing knowledge of effective feedback mindsets and practices and their role in promoting student achievement. The iCoLs “road-tested” the strategies before they were included in any of the sessions, so they were clear about how (and if!) they worked.

The planning sessions were characterised by collegiality and collaboration enacted through learning-focused discussions. I supported the process by providing appropriate and engaging research and resources. However, the planning process was organic, iterative and itself guided by the principles of assessment for learning. We set learning intentions and success criteria for our planning meetings and for each of the morning PLG sessions we delivered. A key target was for every session to begin with teacher reports about strategies they had trialed and to end with at least one “takeaway” strategy and an expectation that it would be used in the week ahead. Our theory for improvement said that students needed time to respond to and act on feedback and we chose strategies that provided opportunities for students to correct misunderstandings and improve content.

The nine morning sessions were developed/co-constructed via three day-long planning workshops. The second and third workshops began with review and reflection on the sessions that had already been delivered and we shaped the next phase of the learning with that feedback in mind. Our reflection included assessment of teacher engagement with and understanding of the content that we gathered using a range of strategies.

Central to developing the leading learning capabilities of the iCoLs was observation of practice and Practice Analysis Conversations. The iCoLs and the facilitator met to agree a focus for the observation, the facilitator observed the iCoL leading their PLG and both then discussed the “session” and agreed next steps for practice. The observations also provided a key opportunity to gather learner voice (in this case the PLG members) that was used in the planning of subsequent sessions and to evaluate the impact of the PLD.

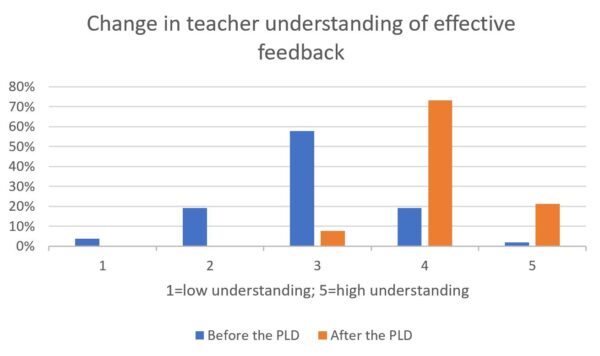

We gathered data about teachers’ mindsets and feedback practices at the beginning and end of the project. We also surveyed students about feedback to enable us to check the validity of teachers’ self-assessment of their mindsets and practices. Teachers’ self-assessment of their use of feedback and their mindsets about teaching and learning and expectations of students all saw significant positive shift. The shift in teacher knowledge and understanding of effective feedback practices is shown in the graph below and was one of the most dramatic and rewarding pieces of data. Coupled with the observations and learner voice, a clear picture emerges of high levels of teacher engagement and learning during this PLD.

The iCoLs also reported increased confidence in leading learning and this was endorsed by the members of their PLGs.

Where to next?

The next phase of the work will develop a line of sight to the main objective: improving student achievement at Merit and Excellence level. The iCoLs will observe the members of their PLG using effective feedback strategies in the classroom and analyse their practice in a subsequent conversation. The students will also be surveyed again to see if they have noticed shifts in their teachers’ mindsets and practices and to gather their view on the impact of any change. And we probably won’t be able to resist looking at NCEA achievement data with our eyes wide open about the dangers of attributing any shifts to this PLD!

The success of the PLD can be attributed to the support from the senior leadership team; the leadership from the Across School leader; the engagement of the iCoLs which was facilitated by involving them in the design. The design of the sessions including clear takeaways and high expectations for implementing new strategies; and the allocation of time for the learning within the mornings. Secondary schools that have struggled to engage teachers in learning and implementing new strategies might want to hear more about the notable success of this work.

This blog was written by Richard Watkinson, a former PLD consultant at Evaluate Associates | Te Huinga Kākākura Mātauranga.

Other articles you might like

A few years ago I visited a school for the first time and a teacher asked what my job was. I told her that I was a facilitator and a lot of my work in schools was supporting teachers and students with assessment for learning. “Ugh… assessment,’ she replied. “If they would just let us get on with teaching!” It was a wonderfully honest response, which demonstrated to me how assessment can start to be viewed as a required task which sits separately to teaching and learning, rather than the bridge between teaching and learning.

As educators, we have all heard inspiring stories of the teacher or mentor who changed the direction of a disengaged student.For me, it is the story of Marcus Akuhata-Brown that remains and resonates in my head and heart.

How ‘open to learning’ are you?